were

targeting.

Sherriff's Department had been spying on a Great Plains Tar Sands

Resistance training camp

that took place from March 18 to March 22 and which

brought together local landowners,

Indigenous communities, and environmental

groups opposed to the pipeline.

On the morning of March 22 activists had planned to block the gates at the

company’s strategic oil reserves in Cushing, Oklahoma as part of the larger

protest movement against TransCanada’s tar sands pipeline. But when they showed

up in the early morning hours and began unloading equipment from their vehicles

they were confronted by police officers. Stefan Warner, an organizer with Great

Plains Tar Sands Resistance, says some of the vehicles en route to the protest

site were pulled over even before they had reached Cushing. He estimates that

roughly 50 people would have participated— either risking arrest or providing

support. The act of nonviolent civil disobedience, weeks in the planning, was

called off.

“For a small sleepy Oklahoma town to be saturated with police officers on a

pre-dawn weekday leaves only one reasonable conclusion,” says Ron Seifert, an

organizer with an affiliated group called Tar Sands Blockade. “They were there

on purpose, expecting something to happen.”

Seifert is exactly right. According to documents obtained by

Earth Island

Journal, investigators from the Bryan County Sherriff’s Department had been

spying on a Great Plains Tar Sands Resistance training camp that took place from

March 18 to March 22 and which brought together local landowners, Indigenous

communities, and environmental groups opposed to the pipeline.

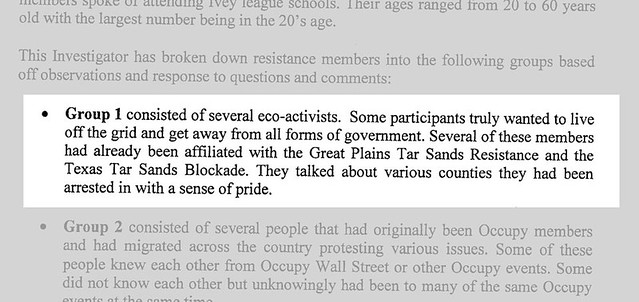

An excerpt from an official report on the "Undercover

Investigation into the GPTSR Training Camp" indicates that at least two

law

enforcement officers from the Bryan County Sherriff’s Department

infiltrated the training camp and drafted a detailed report about

the

upcoming protest, internal strategy, and the character of the protesters

themselves.

At least two law enforcement officers infiltrated the training camp and

drafted a detailed report about the upcoming protest, internal strategy, and the

character of the protesters themselves. The undercover investigator who wrote

the report put the tar sands opponents into five different groups: eco-activists

(who “truly wanted to live off the grid”); Occupy members; Native American

activists (“who blamed all forms of government for the poor state of being that

most American Indians are living in”); Anarchists (“many wore upside down

American flags”); and locals from Oklahoma (who “had concerns about the pipeline

harming the community”).

The undercover agent’s report was obtained by Douglas Parr, an Oklahoma

attorney who represented three activists (all lifelong Oklahomans) who were

arrested in mid April for blockading a tar sands pipeline construction site.

“During the discovery in the Bryan county cases we received material indicating

that there had been infiltration of the Great Plains Tar Sands Resistance camp

by police agents,” Parr says. At least one of the undercover investigators

attended an “action planning” meeting during which everyone was asked to put

their cell phones or other electronic devices into a green bucket for security

reasons. The investigator goes on to explain that he was able to obtain

sensitive information regarding the location of the upcoming Cushing protest,

which would mark the culmination of the week of training. “This investigator was

able to obtain an approximate location based off a question that he asked to the

person in charge of media,” he wrote. He then wryly notes that, “It did not

appear…that our phones had been tampered with.”

(The memo also states that organizers at the meeting went to great lengths

not to give police any cause to disrupt the gathering. The investigator writes:

“We were repeatedly told this was a substance free camp. No drug or alcohol use

would be permitted on the premises and always ask permission before touching

anyone. Investigators were told that we did not need to give the police any

reason to enter the camp.” They were also given a pamphlet that instructed any

agent of TransCanada, the FBI, or other law enforcement agency to immediately

notify the event organizers.)

The infiltration of the Great Plains Tar Sands Resistance action camp and

pre-emption of the Cushing protest is part of a larger pattern of government

surveillance of tar sands protesters. According to other documents obtained by

Earth Island Journal under an Open Records Act request, Department of

Homeland Security staff has been keeping close tabs on pipeline opponents — and

routinely sharing that information with TransCanada, and vice versa.

In March TransCanada gave a briefing on corporate security to a Criminal

Intelligence Analyst with the Oklahoma Information Fusion Center, the state

level branch of Homeland Security. The conversation took place just as the

action camp was getting underway. The following day, Diane Hogue, the Center’s

Intelligence Analyst, asked TransCanada to review and comment on the agency’s

classified situational awareness bulletin. Michael Nagina, Corporate Security

Advisor for TransCanada, made two small suggestions and wrote, “With the above

changes I am comfortable with the content.”

Then, in an email to TransCanada on March 19 (the second day of the action

camp) Hogue seems to refer to the undercover investigation taking place. “Our

folks in the area say there are between 120-150 participants,” Hogue wrote in an

email to Nagina. (The Oklahoma Information Fusion Center declined to comment for

this story.)

It is unclear if the information gathered at the training camp was shared

directly with TransCanada. However, the company was given access to the Fusion

Center’s situational awareness bulletin just a few days before the Cushing

action was scheduled to take place.

In an emailed statement, TransCanada spokesperson Shawn Howard did not

directly address the Tar Sands Resistance training camp. Howard described law

enforcement as being interested in what the company has done to prepare for

activities designed to “slow approval or construction” of the pipeline project.

“When we are asked to share what we have learned or are prepared for, we are

there to share our experience – not direct law enforcement,” he wrote.

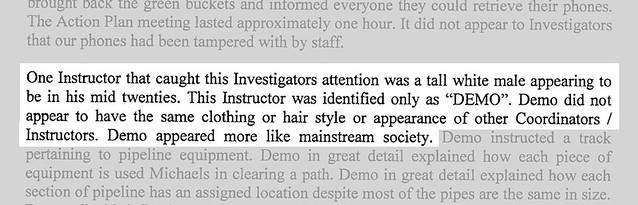

At least one of the investigators seemed to have gained

the trust of the direct action activists.

The evidence of heightened cooperation between TransCanada and law

enforcement agencies in Oklahoma and Texas comes just over a month after it was

revealed

that the company had given a PowerPoint presentation on corporate security to

the FBI and law enforcement officials in Nebraska. TransCanada also held an

“interactive session” with law enforcement in Oklahoma City about the company’s

security strategy in early 2012. In their PowerPoint presentation, TransCanada

employees suggested that district attorneys should explore “state or federal

anti-terrorism laws” in prosecuting activists. They also included profiles of

key organizers and a list of activists previously arrested for acts of

nonviolent civil disobedience in Texas and Oklahoma. In addition to

TransCanada’s presentation, a representative of Nebraska’s Homeland Security

Fusion Center briefed attendees on an “intelligence sharing role/plan relevant

to the pipeline project.” This is likely related to the Homeland Security

Information Sharing Network, which provides public and private sector partners

as well as law enforcement access to sensitive information.

The earlier cache of documents, first released to the press by Bold Nebraska,

an environmental organization opposed to the pipeline, shows that TransCanada

has established close ties with state and federal law enforcement agencies along

the proposed pipeline route. For example, in an exchange with FBI agents in

South Dakota, TransCanada’s Corporate Security Advisor, Michael Nagina, jokes

that, “I can be the cure for insomnia so sure hope you can still attend!”

Although they were unable to make the Nebraska meeting, one of the agents

responded, “Assuming approval of the pipeline, we would like to get together to

discuss a timeline for installation through our territory.”

The new documents also provide an interesting glimpse into the revolving door

between state law enforcement agencies and the private sector, especially in

areas where fracking and pipeline construction have become big business. One of

the individuals providing information to the Texas Department of Homeland

Security’s Intelligence and Counterterrorism Division is currently the Security

Manager at Anadarko Petroleum, one of the world’s largest independent oil and

natural gas exploration and production companies. In 2011, at a natural gas

industry stakeholder relations conference, a spokesperson for Anadarko compared

the anti-drilling movement to an “insurgency” and suggested that attendees

download the US Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Manual.

The infiltration of the Great Plains Tar Sands

Resistance action camp and pre-emption of the

Cushing protest is part of a

larger pattern of government surveillance of tar sands protesters.

LC Wilson, the Anadarko Security Manager shown by the documents to be

providing information to the Texas Fusion Center, is more than just a friend of

law enforcement. From 2009 to 2011 he served as Regional Commander of the Texas

Department of Public Safety, which oversees law enforcement statewide. Wilson

began his career with the Department of Public Safety in 1979 and was named a

Texas Ranger — an elite law enforcement unit — in 1988, eventually working his

way up to Assistant Chief. Such connections would be of great value to a

corporation like Anadarko, which has invested heavily in security

operations.

In an email to Litto Paul Bacas, a Critical Infrastructure Planner (and

former intelligence analyst) with Texas Homeland Security, Wilson, using his

Anadarko address, writes, “we find no intel specific for Texas. There is active

recruitment for directed action to take place in Oklahoma as per article. I will

forward any intel we come across on our end, especially if it concerns Texas.”

The article he was referring to was written by a member of Occupy Denver calling

on all “occupiers and occupy networks” to attend the Great Plains Tar Sands

Resistance training camp.

Wilson is not the only former law enforcement official on Anadarko’s security

team; Jeffrey Sweetin, the company’s Regional Security Manager, was a special

agent with the Drug Enforcement Administration for more than 20 years heading up

its Rocky Mountain division. At Anadarko, according to Sweetin’s profile on

Linkedin, his responsibilities include “security program development” and “law

enforcement liaison.”

Other large oil and gas companies have recruited local law enforcement to

fill high-level security positions. In 2010, long-time Bradford County Sheriff

Steve Evans resigned to take a position as senior security officer for

Chesapeake Energy in Pennsylvania. Evans was one of a handful of gas industry

security directors to receive intelligence bulletins compiled by a private

security firm and distributed by the Pennsylvania Department of Homeland

Security. Bradford County happens to be ground zero for natural gas drilling in

the Marcellus Shale, with more active wells than any other county in the state.

In addition to Evans, several deputies of the Bradford County Sheriff’s office

have worked for Chesapeake — through a private contractor, TriCorps Security —

as “off-duty” security personnel. TransCanada has also come to rely on off duty

police officers to patrol construction sites and protest camps, raising

questions about whose interests the sworn officers are serving.

Of course for corporations like TransCanada and Anadarko having law

enforcement on their side (or in their pocket) is more than just a good business

move. It gives them access to classified information and valuable intelligence —

essential weapons in any counterinsurgency campaign.

Adam Federman is a frequent contributor to

Earth Island Journal. You can find more of his work at

adamfederman.com</

No comments:

Post a Comment